A more plausible story for how U.S. healthcare got so messed up

And a plea to sit with complexity.

Picking up where my last post left off on why profit isn’t the problem with American healthcare:

5. Most of the reasons the United States has worse health outcomes have nothing to do with its healthcare system.

The thrust of Luigi Mangione’s written, confessed motive for killing Brian Thompson read:

“the US has the #1 most expensive healthcare system in the world, yet we rank roughly #42 in life expectancy. United[Healthcare]…has grown and grown, but has our life expectancy? No…”

This should sound familiar. Almost every article or stump speech on the failings of U.S. healthcare has this maddening line that we “spend more on our healthcare, but aren’t any healthier for it”—as if we’d expect the causation to go any other way. The truth is that we die sooner and spend more on healthcare in large part because we are less healthy, in ways it’s absurd to blame on the healthcare system.

Americans eat less healthy diets than residents of other rich countries. We live in less walkable cities, so we drive more and exercise less—which leads to more obesity, heart disease, stroke, diabetes, osteoarthritis, and some cancers. It also forces us to drive more, so we have way more car accidents. We have way more violent crime. We have more drug overdoses. Overdoses, gun deaths, and car accidents alone explain about half of the life expectancy gap among men—and Americans also have higher stress levels. We are lonelier. You probably have your own pet theories for why Americans are less healthy, and some of those may even be true.

So yeah: Americans have a lower life expectancy than people who live in healthier societies. And being less healthy, Americans have more health issues that require more treatment. This is not the primary reason we spend more, and it does not exonerate our health system of its massive failings, which I’ll touch on below. Nor does it get our system off the hook for bad outcomes that really are its fault, like maternal mortality. But a huge part of the story for health outcomes is completely external to healthcare policy.

6. Healthcare providers can charge inflated prices because a confluence of policy choices have eliminated cost-consciousness…

In a healthy market, competition and consumer cost-consciousness limit how high and quickly prices can climb. But in the U.S. healthcare system, decades of piecemeal regulation interact with each other in ways that remove those limits. This encourages healthcare providers and suppliers to overtreat and overcharge, and forces private (but not public) insurers to fight back against those practices.

The origins of this system probably lie in WWII price controls, union activism, and postwar tax incentives which taxed non-cash compensation less heavily than regular wages.1 These factors motivated employers to divert ever-higher portions of their employees' compensation packages into health insurance coverage (since a $5,000 health insurance plan would be taxed less than $5,000 in wages, etc.) Demand for more expensive and expansive insurance led to plans that covered even routine healthcare formerly deemed uninsurable. Over time, what was previously insurance against uncertain health risks gradually became mere prepayment for inevitable consumption. The introduction of Medicare and Medicaid turbocharged this trend.

Unfortunately, a third-party prepayment model majorly reduces the incentive to economize on healthcare consumption when you do inevitably visit the doctor. After you hit your deductible, a growing portion of the bill is covered by someone else, and anything charged beyond your out-of-pocket maximum is the same to you either way. In many cases, that gives health providers a major incentive to overtreat, overscan, overprescribe, and overcharge without pushback from reluctant patients, since patients aren’t paying at the point of sale. Whoever provides their insurance—for profit or not—is paying, and the better the insurance is, the more of their bill it covers.

So from the patient’s perspective, sure: give me another scan, just in case. You say my sore throat is probably a virus, but I don’t want to come away empty-handed: prescribe me some antibiotics, just in case. And from the doctor’s perspective: yeah, physical therapy may have just as good outcomes as a $50,000 surgery—but I’ll make a killing if I recommend the surgery, so I’m subconsciously biased towards that. You’ll only pay your deductible, and who are you to argue with the doctor when your back is in pain?

For that matter, why not price the surgery at $90,000? The person deciding whether to go for it won’t give a damn, because they’re not paying the extra 40 grand. Insurance has them covered. The rise of third-party payers allowed healthcare providers to completely untether the price of their products from an individual's ability to pay.2

The historical record is clear that medical services became more expensive in our country after and because they were insured.3 In a book about Medicare, experts Theodor Marmor and Jon Oberlander write:

“In the first year of Medicare’s operation the average daily service charge in American hospitals increased by an unprecedented 21.9%. The average compound rate of growth in this figure over the next five years was 13%...In the eleven months between the time Medicare was enacted and the time it took effect, the rate of increase in physician fees more than doubled, from 3.8% in 1965 to 7.8% in 1966. The average compound rate of growth in physician fees remained a high 6.8% over the next five years. In the first five full years of Medicare’s operation, total Medicare reimbursements rose 72%...Over the same period, the number of Medicare enrollees rose only 6%.”

Of course, this creates a toxic cycle. The more expensive healthcare is, the more people feel they need insurance to protect themselves from that risk. The more insurance they buy, the less they pay out of pocket when they need to visit the doctor, and the more healthcare they can consume on somebody else’s dime. In the early 1960s, Americans paid $1.80 in out-of-pocket health expenses for every $1 paid by a third party. After Medicaid and Medicare were introduced a few years later, it became $1 to $1. Today, consumers pay less than 20 cents out-of-pocket for every $1 paid by a third party.

And today, the amount of medically unnecessary health care provided in the United States is truly staggering. Here are some statistics from the 2018 book Overcharged, with other hyperlinks added where I could find updated figures:

Americans spend $2.4 billion a year on stent procedures, of which up to two-thirds are medically unnecessary.

Maternity wards give three times as many C-sections as they should because surgeries get them and the hospital paid more. This is dangerous and contributes to poor maternal health outcomes.4

Dentists overtreat extensively, often on poor children to maximize their Medicaid payouts.

11-14% of back surgeries meet criteria for overuse, costing Medicare alone over $600 million/year.

One study showed half the people in ICUs were unlikely to benefit from being there, but could be charged more for there than in other beds.

60% of Americans who go to the doctor with a sore throat, 73% of those who come in with acute bronchitis, and half of all flu patients come home with a prescription for antibiotics, despite all of those ailments being viral. Cost estimates vary given the compounding effects of anti-microbial resistance, but are in the billions.

Radiologists do 95 million scans per year, of which many are uselessly low quality—but insurance can’t tell which those are, so it costs us $7.5-12 billion per year.

Medicare sometimes pays by the number of vials of a drug administered. So instead of one 100ml vial, doctors can use four 25ml vials, etc.

Annual mammograms for women aged 40-49 actually do more harm than good, but lobbyists for the doctors performing them launched a successful PR campaign for HHS to recommend them anyway.

All told, a 2012 study in the Journal of the AMA concluded that a reasonable midpoint estimate of total waste in U.S. healthcare spending was 34%. The high end of the range was 47%. (Remember, insurance profits were 0.5%).

Most of this overtreatment is not fraudulent or malicious (see part 8), but plenty of fraud is out there. “A conservative estimate is 3% of total health care expenditures, while some government and law enforcement agencies place the loss as high as 10% of our annual health outlay;” either way, we’re talking hundreds of billions of dollars of fraud by 2023 spending levels.5

Fraud is especially common against government-run systems because Medicare and Medicaid essentially work on an honor system, with not nearly the staff needed to review more than a small fraction of claims. Overcharged explains:

Medicare and Medicaid receive something like three billion claims a year. For a human being to spend five minutes reviewing each claim would require 125,000 people each working 2,000 hours a year. That’s not enough time to find and flag a fraud, much less to investigate one….So most claims are submitted and processed electronically without any substantive review. Computer programs check to see if all of the fields in a bill have been completed as the relevant regulations require and, if they have, the bill is paid.

Those much-touted administrative efficiencies? That’s the result of those programs not checking the claims before paying them, because they have neither the budget nor the motive to do so. In another section, the Overcharged authors put it sharply: “Proponents of Medicare for All treat the paltry amount that Medicare spends on administration as evidence of superior efficiency when it actually reflects the government’s staggering profligacy with taxpayers’ money.”6

7. …and also destroyed competition between providers.

Competition is also essential to controlling costs. But a wide range of federal regulations have restricted competition among doctors, drugmakers, and insurers, further increasing providers’ leverage to increase prices.

Generous U.S. patent law provides de jure monopolies to pharmaceutical companies for decades at a time. These monopolies so inflate prices that brand-name drugs make up 10% of prescriptions filled in the US, but account for over 82% of drug spending. And by making slight tweaks to their drugs and then filing for new patents, companies can extend or “evergreen” these monopolies to keep prices inflated.

Only the wealthiest and best-connected firms can participate in this bonanza, because the FDA maintains enormous barriers to market entry for newcomers. The full gamut of FDA clinical trials costs well over a billion dollars per drug. Asinine prohibitions against importing drugs from overseas (including drugs the FDA has already approved, that are cheaper in other countries) further shield these companies from any need to price their products competitively. The FDA in general is wildly risk-averse in ways that greatly reduce the supply of effective treatments and give makers of approved treatments leverage to hike prices massively and arbitrarily, as they did for Epi-Pens.

Meanwhile, antiquated and protectionist restrictions on medical licensure and medical school accreditation artificially narrow the supply of doctors, giving each more leverage to charge inflated fees. For example, the American Medical Association works to prevent the establishment of new medical schools; restrict how many students the existing medical schools are allowed to train per year; prevent foreign doctors from practicing in the US unless they redo their residency and exams, even if they’ve practiced for decades in their home countries; prohibit qualified nurses or PAs from offering standard treatments for routine illnesses without physician supervision; limit retail clinics and physician-owned hospitals; and go to war against niche healthcare providers like midwives or optometrists due to overblown, statistically unfounded worries about patient safety. Similar protectionist catfights recur in state legislatures all over the country; for example, lobbyists representing nurse anesthetists argue with lobbyists representing physician anesthesiologists over whether they should be allowed to practice independently.7

As a reminder, this is the system the left decries as “free market” healthcare.

None of this means that actual free market healthcare would work or that all government is bad. Adding some price controls, or even nationalizing doctors and hospitals like the NHS, could well improve what we have now. But we have to acknowledge that what we have now is not free markets run amok. There are many things to fix in U.S. healthcare, and some of that will require undoing distortions to the market that government put in place.

8. Policy choices deserve more blame for these problems than greed because self-interest is a constant, and only policymakers have the power and responsibility to manage systemic effects.

Now, maybe some of you read the last two sections and thought, “Gee, Andrew—it sure sounds like profit IS the problem with U.S. healthcare! Look at all the dirty tricks those slimy hospitals, doctors, and pharmaceutical companies pull to increase their profits!” And sure: if you’re predisposed to see greed as the world’s core evil, there is plenty in our healthcare system to validate that belief.

But first, note that this view is still at odds with the narrative from Part I. It implies that the greed at fault for our healthcare debacle is shown not in denying care to make a profit, but providing too much care to make a profit. That difference has enormous implications for the needed policy solutions. It also suggests that murdering Brian Thompson was completely confused.

More importantly, blaming these problems on greed misses important context that casts healthcare provider behavior in a more sympathetic light. At the physician level, many medical decisions rely on subjective judgment calls, and many decisions resulting in overtreatment stem from a sincere desire to ensure their patients’ wellbeing. Subconscious or habitual bias towards in-house options (ex: a back surgeon recommending back surgery instead of physical therapy) can impact those judgments without providers knowingly trying to profiteer.

Also, America’s sue-happy liability laws increase the incentive to overtreat “just in case,” and force physicians to take on expensive liability insurance. Many doctors and health workers are stuck in large hospital bureaucracies that restrict their flexibility, even when those hospitals are nonprofits. And after 11-15 years of undergraduate tuition, Med School tuition, and grueling but low-paid residency, American doctors often find themselves hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt, which understandably makes them feel entitled to their hard-earned payday. Dealing with insurance companies can be just as infuriating for them as it is for patients, and the complexity and impersonality of the process increases the temptation to squeeze out whatever they can.

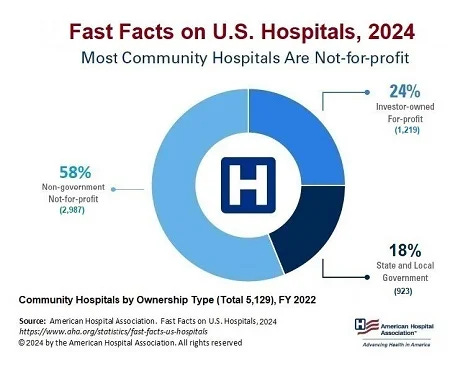

At the hospital level, recall that less than a quarter of U.S. hospitals operate for profit. That doesn’t mean they’re free of self-interest (look at how universities behave!) but it does mean that whatever revenues or efficiencies these hospitals seek are reinvested elsewhere, ostensibly to increase the quality of care or the number of patients they can serve. Public hospitals can face similar incentives.

Likewise, pharmaceutical companies typically reinvest large portions of their windfalls into research that hugely benefits the world. The U.S. pharmaceutical industry is six times bigger than any other nation’s, and many countries with cheaper healthcare free-ride off of American drug innovation. These companies are trying to cure cancer, HIV, Alzheimer’s, and diabetes, and making vaccines for COVID and other diseases that save millions and millions of lives—how can that be bad, they think to themselves? They need money to do it, and the way they can get it is by upcharging insurance companies: by playing the game by the rules our government wrote. Why shouldn’t they evergreen patents for drugs they invented, they reason? It’s not illegal—on the contrary, the law is what gives them the patent.

Self-interest is a constant. We’re very good at justifying it to ourselves. But none of these players are uniquely, especially greedy. In a broadly capitalist society, we should be suspicious of greed as an explanation for why some industries are much more expensive than others. Rather, it is the responsibility of policymakers to design a system that works well even when everyone follows their self-interest. The U.S. healthcare system is broken because U.S. policymakers have failed at that. And one of the reasons they’ve failed is an American political culture incapable of engaging with nuance.

Closing reflections

“Obviously the problem is more complex, but I do not have space, and frankly I do not pretend to be the most qualified person to lay out the full argument.” – Luigi Mangione, in his written justification for murdering Brian Thompson

I don’t usually care enough about healthcare policy to write 5,000 words about it. And honestly, I don’t really care if I’ve convinced you about profit or cost consciousness. I rambled here to make a different point.

My goal in writing this is to nudge people who sympathize with Luigi Mangione to stop cramming complex problems into simplified stories that speak to their biases. Especially as we gear up for Trump II and feel growing temptations towards burnout, radicalization, and violence. Caving to those temptations is surrender to Trumpism, full stop.

It is fine to prefer public to private health insurance. But if you find yourself thinking about people who work in private insurance as cartoon villains who ought to be shot in the street, consider the possibility that you might be high on your algorithm’s supply of rage bait. Consider either broadening your reading on the subject or deferring to experts who have.

The fact that health insurance companies deny 1 in 7 claims is much easier to understand when you learn that many experts think about 1/3 to 1/2 of healthcare spending in the country is medically unnecessary abuse of third-party payment. You still might think insurance companies deny too many claims, or that the tools they use to deny them are too imprecise. But even public insurers need to deny some of them, and figuring out which ones to deny is an enormously complicated task—so it’s really stupid to equate that with murder, just because somebody somewhere makes a profit. And if you do want public insurance to take over, cover everyone, and deny fewer claims, you should admit that this would send healthcare spending way up. The problem of spending more without being healthier would intensify.

Likewise, it’s fine to be angry at the injustice our system produces. The whole system is fucked, so let’s burn it down and break things until they change, right? But if you want things to change for the better, you can’t skip past the step where you think really hard about what, specifically, to break. Otherwise, you wind up shooting the wrong person, other people shoot back, society descends into chaos, and the injustice gets worse instead of better.

As populism surges and experts are marginalized, the stories people tell themselves about the world are going to get even simpler. More validating. Less nuanced. And thus, more expressive of emotion than descriptive of reality. If you want to understand the truth, you have to guard against that. To sit with complexity, even when you’re angry.

According to my source: “One of the most important spurs to growth of employment-based health benefits was—like many other innovations—an unintended outgrowth of actions taken for other reasons during World War II (Somers and Somers, 1961; Munts, 1967; Starr, 1982; Weir et al., 1988). In 1943 the War Labor Board, which had one year earlier introduced wage and price controls, ruled that contributions to insurance and pension funds did not count as wages. In a war economy with labor shortages, employer contributions for employee health benefits became a means of maneuvering around wage controls. By the end of the war, health coverage had tripled (Weir et al., 1988)… A further important boost to these programs came in 1954 when the Internal Revenue Code made it clear that employers' contributions for health benefit plans were generally tax deductible as a business expense and were to be excluded from employees' taxable income.”

This is why most studies indicate Medicare for All would increase healthcare costs even further. Offering more people access to more services at other people’s expense would greatly exacerbate the cost-consciousness problem. And the lower administrative costs are also a fiction: an artifact of older people requiring higher healthcare bills per person, and a reflection of the program’s inability to police fraud or waste.

This principle is underscored by how much cheaper healthcare is in our country when it’s NOT covered by insurance. Examples include vision services like LASIK surgery, eyeglasses, and contact lenses; cosmetic procedures like Botox injections, breast augmentation, dental veneers, and tooth whitening; and elective medical treatments like in vitro fertilization.

“Perversely, doctors who perform C-sections, a surgery that takes about 45 minutes, usually get paid more than those who patiently await vaginal birth, a process that can take hours or days. Hospitals, which also bill more for the surgeries, lack motivation to demand accountability from doctors on staff, which likely incentivizes the procedure.”

These are the crooks I’d be okay with shooting…jk.

This is where those denied claims become easier to understand. The government can afford to be profligate in ways private companies cannot. Unlike the government, private insurance (and even nonprofit insurance like Kaiser Permanente) has to ensure that there’s at least as much money coming in as there is going out. And so unlike the government, private insurance cannot afford to run on an honor system. They have to review medical claims and ensure that they’re medically appropriate and appropriately priced. And if they are not, they have to be willing to deny those claims lest they get absolutely steamrolled by abusive pricing and overtreatment. The resulting back and forth is messy and imperfect and results in some injustices, but it’s absolutely necessary for keeping a lid on healthcare prices.

18 states said yes and 32 said no, pre-COVID, which was surely determined by rigorous science about cost and risk to patients, and not at all by vigorous lobbying from professional organizations with salaries on the line.

There is so much to weigh in on. I’ve watched many independent doctors become the “owned” employed doctors in my 30 year career. And I can speak to that personally. The administratively heavy behemoth hospital organizations incentivize and demand the treatments, because, after all, it is “standard of care.” You no longer could exercise good clinical judgement, let’s say, and evaluate Johnny’s bop on the head with a soccer ball and end it there. It MUST have a Ct scan to rule out a bleed, when you know there are no clinical signs of this. Much of the practicality of medical judgement has been replaced with “standard of technology” and with that technology (radiology, robots in surgery, a-lab-test-for-everything, nanotechnology) comes a high price tag.

For God’s sake, the electronic health record requires its high cost of implementation, management, and cybersecurity. There are many “hidden” costs of doing healthcare business, that add up quickly. So what do we do? We have to pay for this tech somehow, so we incentivize screening tests for prevention or recommend surgeries to use our cool robotic machines.

And to your one point…. Imagine being a physician in a room full of lawyers explaining why you did not use a particular expensive test because it wasn’t warranted….

This is complicated. No doubt. You have done an intricate deep dive. The problems are complicated and the solutions are equally complicated.

Your point about how the American lifestyle is unhealthy is well-taken. I lived in Europe for three years. I’m convinced that Americans would be healthier with simple changes such as walking more and eating healthier food in smaller quantities. Even with desserts we could change things. Desserts in Europe are quite tasty. But they generally aren’t as sweet as American desserts. Europeans are also better about taking time off from work. Europeans aren’t perfect. For example, they took a long time to move away from smoking. Still, if an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure, we could learn a few things from them.