Yes, AI really might steal your career

It’s different enough from prior technologies to outpace the professions’ typical defense mechanisms. Besides, most workers are more vulnerable than true professionals.

Last month,

of wrote an insightful post titled No, AI won’t steal your career. Trust me, I’m a sociologist. The trustworthiness of sociologists aside, her essay makes important points that some in the AI forecasting community may not fully appreciate. It’s also well-written, accessible, and rooted in solid research, making it a useful contribution to the mainstream debate on AI’s social implications.I liked it so much that I decided to rebut it—but only after amplifying what it gets right.1 This post has two parts, which are awkwardly intended for two different audiences. The first part, intended mainly for my readers in the EA community, draws implications from Nova’s core observation and expands on the difference between AI takeoff and AI diffusion. The second part responds to Nova directly, giving two reasons why I don’t think her title follows from that core observation.

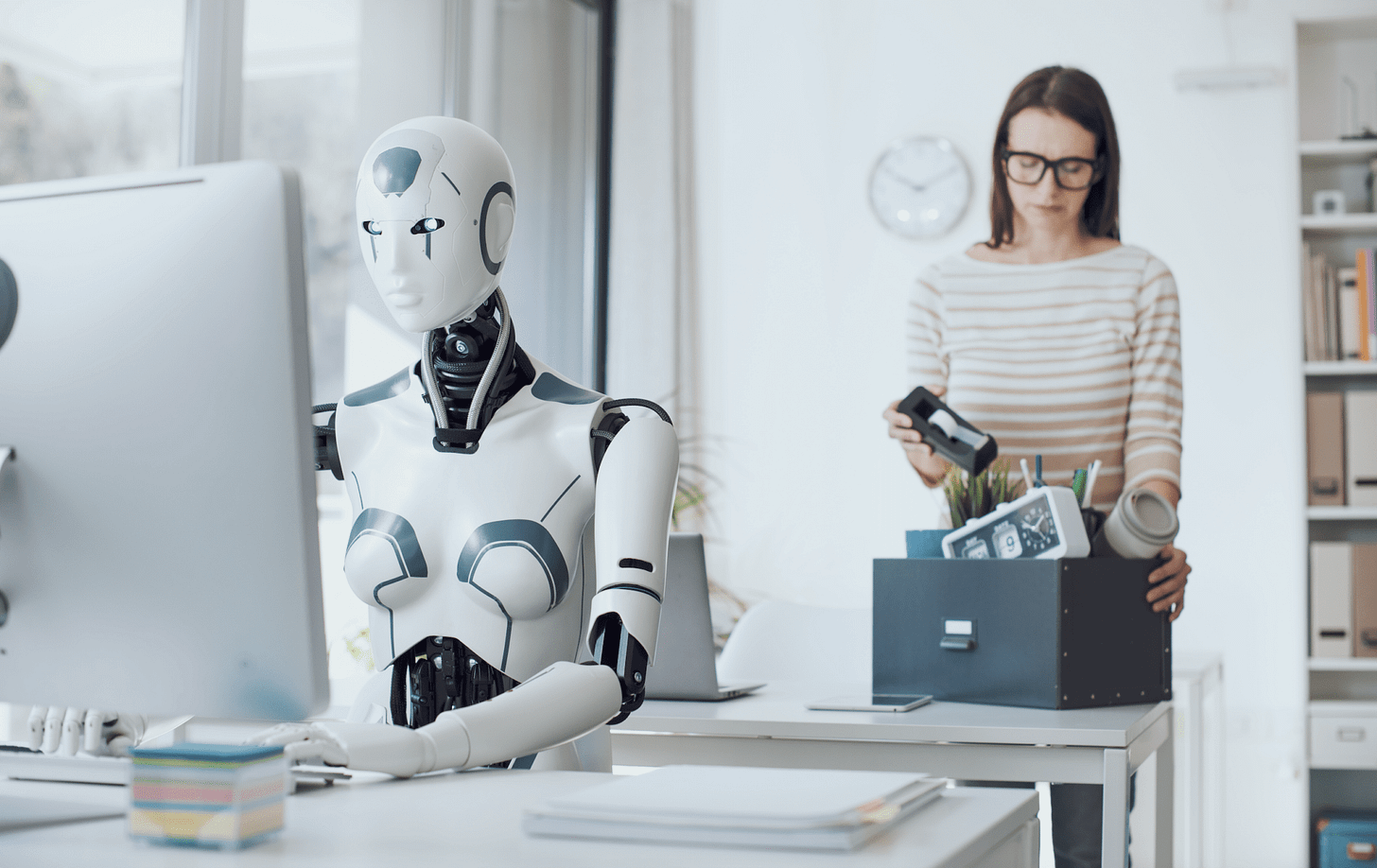

Note: Though this is the best image for AI labor displacement I could find in 30 seconds of searching, I don’t know whether or why the AI would have boobs.

The core observation

Nova claims that the modern workforce is “increasingly dominated by the professional and technical sectors.” And professions, she notes, are not just collections of tasks that could be done by either human or machine. In fact, the specific duties performed by a profession tend to change wildly over time.

Rather, professions are groups of clever people with shared interests and a degree of political power, which they use to take an active part in social decisions affecting their interests. Professions “actively influence and transform their environments,” Nova writes. “They stake claims, fend off threats,” and “fight for jurisdiction over who or what gets to do which types of labor.” She elaborates:

“Professions aren’t just defined by what they do, but by their ability to convince the rest of us that only they can do it. These ideas are reflected in our licensing bodies, educational systems, and regulatory frameworks. For example, physicians are the only profession that we allow to perform surgery on humans, partly due to regulations, partly due to our trust in the field of medicine, and partly due to the profession’s political maneuvering…Jurisdiction over tasks is…something that society grants through cultural processes like laws, norms, and trust.”

Nova thinks AI is unlikely to steal your career because she expects and encourages professions to “actively fight for survival” in the face of the AI threat. “Professions don’t just roll over and die and when new technology appears,” she observes. Historically, most professions have persevered in the face of technological progress through a combination of a) defending their turf from the new machines, b) subsuming the mastery or interpretation of the machines as a task within their jurisdiction, and c) carving out new sets of proprietary tasks which the machines cannot yet replace. She continues:

“This is why we have regulatory boards, licensing bodies, and professional associations…They’ll say it’s for quality assurance, which is partly true—but let’s be real, they also exist to keep the amateurs (and now, the robots) from encroaching on the good jobs. Many professions have protected tasks, and by framing the use of technology as part of these protected tasks, they ensure that automation tools could only be used under their supervision…

This approach often goes hand in hand with making ethical and safety-based claims about the dangers of removing humans from the equation. Highlighting risks, like the potential for AI-driven errors or the lack of empathy in decision-making, can effectively underline the continuing importance of human expertise.”

Nova concedes that AI may affect the workforce, citing one study that estimates one in five workers will have at least 50% of their tasks “impacted” by large language models. But by leveraging social and political power (ex: through op-eds, policy meetings, & professional organizations2) to highlight or play up the risks of removing humans from the equation, she thinks people with careers will be able to keep them, so long as they react in time.

Implications

I think this argument is historically true and continually relevant for AI debates. It’s especially relevant for two groups of people.

The first group is licensed or unionized professionals. Nova is right that many professions have some power to defend themselves from automation, like Hollywood actors and writers did in 2023. Just because an AI system may become capable of doing a professional’s job doesn’t mean that the profession’s power and connections won’t be able to create certain hiding spots where AI isn’t permitted to go. It's up to you if securing those hiding spots is your top priority in the face of the coming storm.

The second group are those who expect advanced AI to not only have very fast takeoff speeds, but also fast diffusion speeds, such that they displace almost all human labor in just a few years. These concepts are often blurred together in discussion of AI “timelines,” but they warrant distinction.

Roughly, takeoff refers to how quickly the capabilities of frontier AI models will reach and surpass human-level intelligence.3 The debate over takeoff speeds is very technical and requires knowledge of computer science. Diffusion, by contrast, refers to how quickly AI is integrated into products, services, systems, and robots that perform useful work—and (relatedly) how quickly it is permitted to do that work. Assessing diffusion timelines requires a broader understanding of political, economic, and sociological factors, which computer science people have not necessarily studied.4

Nova’s argument supports the idea that even if AI takeoff winds up being fast, AI diffusion may not be. I agree with this idea, and suspect that some in the AI community are naively skimming over the diffusion challenge when envisioning their AI timelines.5 The fastest AI timelines seem to assume that not only will AI quickly become capable of replacing most workers, but that it will almost as quickly (ex: within a single presidency) take over the military, the courts, most doctors and businesses, etc. They assume we live in a rational and efficient enough society for labor displacement to primarily depend on whether the technology is good enough to replace people with wealth, education, and power.

To defend this assumption, those expecting fast diffusion typically argue that it will quickly become apparent that AI provides massive advantages across sectors. Anyone who doesn’t integrate it will quickly be left behind, creating strong incentives for rapid adoption. In some contexts, this may be true. But in other contexts, it underestimates how much power the judges, lawyers, professors, generals, officers, pilots, surgeons, dentists, optometrists, etc. have to prevent their replacement, even if it does result in some industries, consumers, or nations being left behind.

On aggregate, the Jones Act creates significant economic and strategic harm for the United States. But it’s persisted for over a century because these costs are diffuse, while the benefits are concentrated in a vocal, politically salient industry. Likewise, the defense budget makes inefficient investments in antiquated weapons platforms and military bases because they create jobs in the districts of powerful Congressmen. Also, Navy and Air Force pilots are respected interest groups that fight the adoption of unmanned aircraft—etc.

So whenever superhuman AI is created, its mere existence may not be enough to radically transform society (much less, to take literally all of the jobs). Such a transformation may also require that the AI is entrusted with significant resources and decision-making power across the business, government, and military communities. The raw capabilities of automated systems relative to humans will not be the sole (and perhaps not even the primary) determinant of whether machines are given this trust.

What Nova gets wrong

Still, Nova’s analysis has blind spots of its own that make her title inapplicable to most people. I’ll touch on two of them.

First, I think she is empirically wrong that the “professional and technical sector makes up nearly 3 in 5 American workers (and counting).” Though professions are hard to define, the share of American workers who have the power to put up a meaningful fight protecting their jurisdiction from AI is surely lower than 3 in 5.

Nova’s source for this claim is the Department of Professional Employees at the AFL-CIO—one of the largest labor unions in the country. Intuitively, this source has some incentive to exaggerate the share of the country affected by its work. They claim professionals were 57.8% of the workforce in 2023—but when you look at the fine print, they’re actually counting any worker in the country who has at least a two-year associate’s degree, “given the fluidity of professional identity.” This strikes me as pretty absurd. Your local barista could have an associate’s degree—they could have a master’s degree!—but they are not a professional.

An alternative method, favored by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), includes all workers in the “management, professional, and related occupations” sectors, which they divide into ten categories. Among these, they include all management occupations; business and finance operations; computer and mathematical occupations; architecture and engineering; life, physical, and social sciences; community and social services; and all of arts, design, entertainment, sports, and media occupations. This methodology returns an estimate of 44% of the U.S. workforce. But again, plenty of workers in these sectors are not what we typically envision as professionals, and are not protected by licensure laws.

When I think of true “professions,” I think of lawyers, doctors, teachers, military officers, clergy, and arguably a small handful of others. Professions are typically set apart by the need for a) years of highly specialized education, and b) a government license in order to legally operate.6 What gives professions such comparative esteem is the fact that most people are not professionals. Most don't even have an undergraduate degree, let alone a law degree or an M.D. They do not have a state-issued license, nor access to the levers of political power that would be necessary to invent and print one.

In lieu of professions, what most people have instead are just jobs. Jobs that any old company is allowed to just do, with a machine or without. While professions can adapt by clawing out a space for themselves where the law says computers can’t go (typically to everyone else’s detriment, might I add), most people cannot claw out anything. Most people are simply uprooted by technological changes affecting their industry, unable to buy enough stability to keep the wheel from churning.

Nova gives the example of librarians, which Google tells me typically need a Master’s degree and have state licensing boards. But Google also tells me that librarians are a whole lot fewer in number today than they had been. From 1999-2015, the number of librarians nationwide fell by 20%; it’s likely shrunk further in the decade since. Automation has likely hurt bank tellers and airport check-in workers even more.

So for most people, the reassurance that AI isn't coming for them is probably premature. It isn’t op-eds that define the rules of the licensing board—usually, it’s money and power. And even if it were, most Americans are not smart or educated enough to write a convincing op-ed (pretty soon, AI will be better at that, too). It’s only the highly skilled—or more cynically, the privileged, elite ruling class who write the rules and then adapt to them—that get the state-issued protection.

That’s the first reason AI could steal your career. The second is, the tide is rising faster this time, so it’s harder to evade it by dashing to higher ground.

Nova explains how new technology typically creates new types of work that displaced laborers may be able to take on instead. Historically, that’s been true. But the core argument of the people most worried about AI labor displacement is that this time, it’s different. Unlike prior eras, there’s reason to believe this machine will create new types of work at which it is already better than human beings. And unlike prior technologies, there’s reason to think AI systems will learn, improve, and replicate at marginal costs with minimal physical restraints.

This time, the machines’ abilities are no longer increasing linearly and steadily within their narrow domains. This time, they are rising generally and exponentially in nearly all economically useful domains. This time, changes that previously took generations will be crammed into a year. This time, people who could previously adapt to Plan B will find that the machines are already taking Plan B; that retraining a human for new jobs takes months, while retraining AI for the job takes minutes. So this time, the people can’t adapt—all that’s left is the “die” part.

It's possible that theory is not true, but if it’s not, we’d need a different argument to show it.

Also…the bit I quoted earlier talks about how professions defending themselves “goes hand in hand with making ethical and safety-based claims about the dangers of removing humans from the equation.” But what if pretty soon, those dangers are no longer real? What if you’re a recruiter, or a programmer, or a graphic designer, and it turns out your former bosses or customers can’t tell the difference between your outputs and those of the program they just installed?

What if this even becomes true of the classic professions? What if the machine’s programmed imitation of empathy and judgment is simply a better doctor than the faulty flesh-and-bones version with a fading memory? Not just smarter, but gentler and more attentive than the human doctor set in his ways, who’s sometimes distracted or in a bad mood?

What if, within 10 years, the ethical and safety-based arguments for human professionals are just self-interested baloney? What if protectionist laws just increase prices and decrease quality for everyone, in order to pay rents to a relative few?

In that case, instead of urging professionals to defend their turf, wouldn’t it make more sense to just sever the link between work and financial resources in the first place?

Conclusion

Nova closes by mentioning that privileged white-collar professionals are often the last ones to take transformative technology seriously. Again, I agree. But it seems to me that Nova herself falls into this trap, by significantly underestimating the extent to which AI is about to change the world. In our lifetimes! Maybe not before Trump leaves office, like my friends who are naïve about diffusion bottlenecks think; but like, faster and more significantly than smartphones changed the world. Quickly and significantly enough that it becomes a defining before and after moment in all of our lives, which our grandkids (God-willing…) will be in awe that we lived before.

Unfortunately, I have little idea of whether that change will be for the better.

Some calligraphers survive today; but for the most part, the printing press put scribes out of business. Some indigenous women can squeeze out a living today by selling novelty textiles they made using ancient hand loom techniques; but for the most part, the industrial revolution put hand-weavers out of business.

In similar fashion, some of today’s professionals may be able to weather the coming storm for a while, whether through protectionist laws or catering to lingering demand for artisanal human-made products. But if machines are genuinely, substantially better at almost all economically valuable work, and significant competitive advantages accrue to whoever uses them most, there will eventually be limits to how many workers can keep their jurisdiction human. Professional or not, your career could be in trouble.

Soon after writing her post, Nova subscribed to my newsletter, which further proves her intelligence and fair-mindedness. I’m mostly responding because the topic is relevant to my readers in the EA community, but also to engage with a new subscriber and hopefully send her some more followers, too.

These were her examples, not necessarily strategies I expect to be effective.

Also known as AGI, or artificial general intelligence.

There are also other bottlenecks, like construction speeds, but I’m simplifying.

If your path to AI doom is closer to MIRI’s, and you think that ASI will very quickly escape human control, such that the game is up as soon as it’s created, this critique may not apply to you.

Or, in the case of the priesthood, official ordainment by some other established body.

I don't necessarily disagree with you here, but I think the main argument against AI automating all jobs away is that many jobs nowadays are about coordination between institutions, product releases around consumer trends, etc. AI will be super productive, but I don't think people will trust it more than other people because we can't hold it accountable for mistakes in the same way we can hold other people accountable. I actually have a post scheduled for tomorrow talking about just this (and another one Tuesday why I am not worried about AI from a stereotypically economic perspective). Great post!

Everyone seems to be focused on the question of if and when AI will replace all human jobs, but I think the bigger concern is not over when it will happen but how fast. That is, how long will the transition period between a totally human-dominated and totally AI-dominated economy be? What will be the time interval between the moment that AI first replaces a large sector of the job market in such a way that those workers can't easily get a different job or modify their job to incorporate AI and the time when AI has replaced so many jobs that human labor is virtually obsolete?

This matters the most to me because that transition period is going to be really difficult. If AI replaces all human work, or so much of it that you don't need the incentive of, "You must work to make a decent living," to get people to do the remaining jobs, then it seems like we don't actually have a big problem economically. As you suggested, we can just implement UBI to sever the link between work and financial resources. But it's not like we're just going to immediately switch from the current economy to one like that. There will be some point when AI is powerful and diffused enough to replace some labor but not all, causing mass unemployment, but where human labor is still necessary, so implementing UBI could cause a disastrous economic collapse by removing the incentive to work for those who still have to.

If that transition period ends up being really short, that's great news - things might suck for a little bit, but we'll come out the other end okay. But if it ends up being long, something pretty drastic is going to have to be done to deal with it, and I don't really have any idea what.