Liberals should keep using scorn and mockery

Sharp language is the peaceful way to fight those who refuse to reason.

I wrote a lot last year about how—with what tone or rhetoric—to talk about our politics. Moving forward, I plan to write about this less.1 But I want to squeeze in a final word, partly because two prior posts promised to do so. The question I return to is:

How wide is the range of ideas, behaviors, or political figures that we ought to engage with civility and respect?

There is broad agreement that the woke left narrowed this range too much at the peak of its social media hegemony, and that Democrats and elite institutions lost trust with normal people as a result. For example, it was once common on social media to shame, mock, or ostracize people for:

Cultural appropriation

Misgendering someone

Defending some police killings of unarmed black men, or being skeptical of Black Lives Matter or the 1619 Project (ex: “All Lives Matter”)

Refusing to acknowledge “privilege” or disagreeing with tenets of third-wave feminism

Simply disagreeing with the left on abortion, immigration, capitalism, gun control, or other hot-button issues.

Let’s call this List A. Almost everyone can now see that efforts to shame List A overstepped, even if you side with the left on the underlying issue. For public shaming to be effective, there needs to be a critical mass of society that already agrees the conduct is beyond the pale; progressives too often overplayed their hand where no such consensus existed. I spent much of the 2010s warning them that they were doing this, and on Substack, I’ve found a heartening recommitment to good faith exchange by people on both sides.

But there is also a school of thought on Substack that I think overcorrects. It implies that the range of ideas, behaviors, and political figures that should be treated with respect is effectively unlimited—or at least, contains the entirety of today’s Republican Party. So even when liberals lambast specific conservatives for things on List B….

Naked corruption and criminal activity

White supremacy (ex: Nick Fuentes) or white Christian nationalism

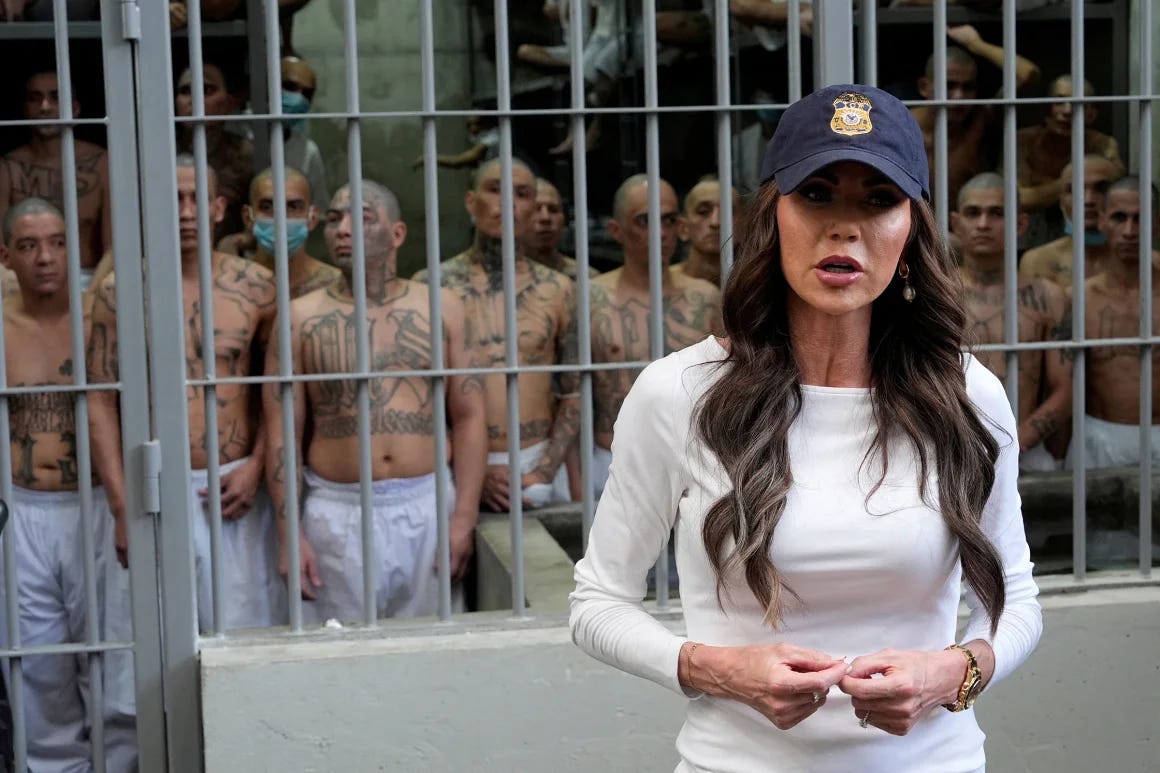

Performative cruelty (ex: CECOT) against outgroups

Attempts to overturn an election, or believing/propagating the Big Lie

Intentional, habitual lying about the very basics of what’s going on

…this school of thought carries on as if those complaining were just haughty, closed-minded elites who’ve forgotten how to persuade. The dumbest or most dishonest among them deny that list B is happening at all (“Trump Derangement Syndrome”) or pretend Democrats did it first or worse. But there are also sane critics of the administration who think the left needs to soften its tone or change the subject if it wants to regain voters’ trust. Here’s why I disagree.

The conservative deflection

The school of thought I’m referring to varies in its sophistication and partisan allegiance, but I’ll link to a few examples so you know I’m not fighting air. On the least compelling end of the spectrum are people engaged in List B themselves (ex: JD Vance2) or the unthinking mouthpieces who carry their water. For example, when Elon Musk dismantled USAID in a way that likely caused millions of deaths, vague screeds like The Unseemly Scorn of the Intellectual Elite pretended that those outraged were just “contemptuous of anyone who dares think or vote differently.”

A step in from there are more moderate conservatives with a persecution complex. For example, @Kitten got 400 likes and 78 restacks for a subtitle claiming “Gay men in the 50s were less closeted than moderately conservative couples in blue metros.” Because getting disinvited from Friendsgiving is apparently equivalent to regular police harassment, or the hundreds of hate crimes in which gay men were beaten, burned, or stabbed to death. One side is starving the poorest people on the planet and deporting legal residents for political speech while the other is being rude on BlueSky—but yes Kitten, start another stanza of Swing Low, Sweet Chariot.3

(I have especially little sympathy for these people because I was an uncloseted libertarian for the entire relevant decade, with the predictable result that nothing bad happened to me at all. So I know the real reason these people are closeted, which is that they are sheepish about who Trump is and embarrassed to have voted for him. Nobody who voted for Mitt Romney needed to stay in the closet about it, and that’s not because liberals got so much less tolerant between 2012 and 2016. It’s because the Republican on the ticket was so much more shameful, and supporting him more blameworthy. It is pure defense mechanism to imagine that your friends think less of you over run-of-the-mill disagreements on abortion or crime, when actually it was the routine corruption and sexual assault and election stealing and firehose of crass, rambling nonsense and…)

A step in from there are people who claim to be persuadable, but only if you treat them super nicely. This, of course, is not how reasoning works. See the supercilious, self-important, utterly fake conditions on persuasion in Persuasive Beats Abrasive by Robert Graboyes. “You won’t persuade me,” lectures this Republican voter, if you speak loudly and angrily; use disputed labels like fascist; fail to condemn political violence in unalloyed terms; traffic in disproven accusations; or lack empathy for your adversaries. Never mind that Trump does every one of these things at every opportunity, and yet has (in Robert’s words) “persuaded millions of Democrats to switch sides.”4

People like Robert seem to imagine their brains are an object of fascination to liberals, as if we were all incredulous at how anyone intelligent could vote as they do. We’re not incredulous. He’s not that complicated—he’s just biased and bad at prioritization. His vision is clouded by some deeper grievance that makes him much more sensitive to one side’s rhetorical oversteps than the other’s; that makes his memory impervious to a daily avalanche of dishonesty from Republicans, yet latch onto the misleading coverage of “Very fine people on both sides,” so that seven years later he can pretend the two sides are the same.

What these writers want most of all is for us to believe that Trump’s victory means we have to take them seriously.5 As if that made the same vapid arguments we’ve refuted 100 times any more compelling than they were in 2018 or 2022.

Like me, these writers were aggravated by progressive excesses. Unlike me, they chose to express that aggravation in a destructive and self-centered way. They voted for the reaction it would provoke, like a 5th-grader testing the waters with “shit” around Mom so she knows he’s SO mad. And now they are crossing their arms, stomping their feet, and demanding some kind of apology; a vindication that actually, they weren’t being stupid and shallow this whole time, it was the left that made them do it by being so judgy and mean.

Liberal elites face a genuine need to empathize with the feelings and concerns of everyday people. They should not confuse it with a need to cater to the emotional hangups of conservative elites. Contrary to what these conservatives would have us believe, MAGA Republicans really are doing reprehensible things that a critical mass of Americans look down on; this can and should be shamed and mocked without alienating half the country; and this really is more important than relitigating affirmative action and media bias for the 500th time, including to the median voter.6

Sometimes the best way to persuade is to be civil and patient and an active listener. Other times, the most efficient way to persuade as many people as possible is to cut your losses with those closed to persuasion. Sometimes abrasive is persuasive—not to the berated person, necessarily, but to third-party onlookers who can tell which side got whipped by someone speaking plainly from the heart, with no filter or safe space for your onerous conditions. Trump and his movement understand this. We should too.

Suppose you agree with me that there are areas where the left overused shame for innocuous or borderline conduct; and also, other areas where the conduct is so revolting that shame is perfectly warranted. The question then becomes: which matters more to you?

From my perspective, the stakes of these issues are wildly asymmetrical.7 On one side is your selfish safety from social censure in a handful of sensitive cases that rarely come up, and that socially competent people can usually avoid in mixed company. And on the other side are moral stakes that seem truly gargantuan to anyone who actually gives a shit. Whether our country can effectively govern itself, or devolves into a corrupt autocracy; whether it’s policies, courts, and massive budget will be guided by evidence and empathy, or devolve into tribal idiocy; whether it’s spiteful, unstable leaders will be constrained by crucial guardrails, or be set loose to ignore Congress, ignore term limits, crack down on dissent, and brutalize peaceful people indefinitely.

So the more you fixate the areas where shame was overused, the more convinced I become that you are the one with the tribal mind virus that’s diseased our politics, of which wokeness is only a subset.

The liberal overcorrection

Not everyone who sympathizes with this school of thought is of the right. I’ve already engaged with two on the center left: Ezra Klein and Daniel Muñoz.8 Some in the “abundance” crowd make similar arguments.

For the most part, these people just want to turn down the political temperature and adjust Democrats’ messaging after the 2024 defeat, both of which are laudable goals. They may personally acknowledge a distinction between Lists A and B, but they worry that distinction is not as apparent to swing voters, who understandably care less about moralizing and more about tangible impact on their lives. They also worry that the left crying wolf over List A has undercut the effectiveness of using shame in any context, and that Democrats seem out of touch in part because they sound like moral scolds.

Setting aside the electoral implications, policy wonks tend to enjoy good faith discourse and share my exasperation at watching people talk past each other. They don’t want that process to be frustrated by either side feeling attacked, and they’re “done waiting” for the other side to be civil first. Klein, Muñoz writes, “has been trying out a critique of the current American left: that it’s so enamored with shaming, it’s given up on talking.” And Muñoz himself argues:

“the shunning of bad faith interlocutors…is toxic sludge being pumped into the civic infrastructure of our democracy. It’s poisoning the way we think about one another, and it’s clogging the only channels we have left for meaningful conversation and persuasion.”9

In short, they think the liberal way forward is to immediately defuse Americans’ anger, while I think the better strategy is to harness and focus it. I have two reasons for believing this.

First, softening our tone is politically unnecessary, and probably counterproductive against populist incumbents at a moment of global unease. The narrative that liberals drove voters into Republicans’ arms because of their tone is most obviously undercut by Republicans’ tone, which has been even sharper for just as long. The right uses scorn and mockery all the time, and that does not stop them from picking up swing votes.

In calling on liberals to adopt a more civil tone, Ezra Klein said he was “envious” of the media empire Charlie Kirk built. But how did Kirk build it, if not through constant mockery and rage bait? What did Klein mean by Kirk’s “moxie and fearlessness” if not his willingness to speak in such an inflammatory way?

People say we need a Joe Rogan on the left. I agree liberals need to speak with less of a filter. But Rogan does not hold elevated debates firmly rooted in the best available evidence; he just nods along to whatever pothead bullshit his audience wants to hear. We can take the high road, or we can take a page out of the right’s book, but we definitely cannot do both.10

A more plausible contributing factor to Democrats seeming out of touch is that we sound like nerds in debate club, oblivious to the emotional forces that actually drive today’s politics. More than ever, liberals need to engage with the emotional side of politics too, and that requires a different toolkit than abundance wonks typically offer.11

In this sense, trying to elevate the left’s rhetoric actually heightens the contrast between how we think and how ordinary people think. I’ve explained several times how populism discredits and crowds out intellectual discourse as a deliberate strategy.12 It is not only that the administration uses scorn and mockery to accompany its arguments; it often uses them to replace arguments, leaving nothing of substance for liberals to engage. The Sartre quote applies:

“Never believe that anti-Semites are completely unaware of the absurdity of their replies. They know that their remarks are frivolous, open to challenge. But they are amusing themselves, for it is their adversary who is obliged to use words responsibly, since he believes in words. The anti-Semites have the right to play. They even like to play with discourse for, by giving ridiculous reasons, they discredit the seriousness of their interlocutors. They delight in acting in bad faith, since they seek not to persuade by sound argument but to intimidate and disconcert. If you press them too closely, they will abruptly fall silent, loftily indicating by some phrase that the time for argument is past.”

Engaging credulously with these “““arguments””” risks falling into their trap. At best, they amuse themselves; at worst, they aim to intimidate, disconcert, and discredit the endeavor. It’s harder for them to do that if nobody plays ball, and even harder when people call out and condemn their tactics.

Maybe some liberals are “so enamored with shaming they’ve given up on talking.” In my case, it would be more accurate to say I’m so exasperated by talking that I can’t begrudge the shaming. Trying to reason with Laura Loomer is like Charlie Brown trying to kick the football that Lucy promises to hold still: it does more to make us look foolish than it does to build trust.

A better lesson for Democrats from 2024—not just from the US, but from elections around the world—is that anger with the status quo is the most powerful political force in the democratic world today.13 To restrain our most authentic and relatable expressions of this widely shared emotion would handicap our ability to connect with normal people.

Much hay has been made over how woke culture made conservatives feel: condescended to, preached at, alienated, demonized. This is regularly framed as something liberals are responsible for, and as justification for why 77 million Americans voted for a corrupt child rapist felon who tried to steal an election. Fine.

The left has feelings too, and we cannot hold them to such uneven expectations for how to react to those feelings. That would impose an absurd double standard in how much patience, self-awareness, strategic thinking, and resistance to peer pressure we expect the two tribes to exhibit. It’s not just that it’s unfair or a bad idea: we couldn’t change how something as big as “the left” feels and writes if we tried.14

Even if it were possible, softening the left’s rhetoric would neuter the only political momentum it has, and the greatest advantage it has as the opposition party. Huge swaths of the country are genuinely livid at what Trump is doing. No Kings protests are well attended. Gavin Newsom has emerged as a frontrunner precisely because his combative social media presence.15 Voters want Democrats to fight, even if not for progressive priorities. Combining the moderate policy of Andy Beshear or Josh Shapiro with Newsom’s social media bravado seems like a winning formula.

That doesn’t mean we should stoop to the right’s level and weaponize emotions with no regard to the truth, nor endorse or trivialize violence. But cursing out a reporter? Calling your opponent a fucking idiot? Telling the courts to grow a pair? That’s what combative centrism looks like.

Democrats must control their anger, but that’s not the same as calming down. They may need to moderate some policy positions, but they should not moderate their tone. Sounding angry is a political necessity right now.

The second reason is more esoteric. Set aside how to fight; what are we fighting for, and how can it endure? Voters need to know that, too—and so do we, if we want to feel less lost.

To articulate a positive vision of what we stand for, it is helpful to distinguish the real thing from its toxic imitation. My chosen political communities are fighting for popular concepts—moral progress, and a rational public discourse—that the New Right can only pretend to care about. Mocking the imitation brings that distinction into sharper relief, while assuming sincerity on the part of the impostors helps them blur boundaries that are central to our appeal.

To illustrate: Liberals think policy should be made through good-faith, evidence-rooted discussion between curious people seeking compromise and coexistence in a pluralistic world. Such a flowering dialogue is not a hardy weed. It can only thrive under certain conditions.

Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò has reflected thoughtfully on those conditions, and explained why one of which is shame itself. Liberal societies have a high bar for state coercion—high enough to permit a lot of socially detrimental behavior. For such societies to work, there need to be other deterrents for that conduct that have a lower bar. Social stigma is chief among these. By scorning and mocking reprehensible behavior, liberals are policing guardrails essential to the sustainability of the liberal project:

“Common decency, then, stigmatizes people who do not participate in it—removes them from voluntary association, as Russell exemplified. We indeed have to live with one another, but terms and conditions apply…

Shame serves as a robustly liberal alternative to the political violence that Klein and company rightly abhor. It is, quite literally, the least one can do to ensure rules of social conduct that uphold minimal levels of dignity for all involved. Most of the alternatives involve either subjugation, combat, or both. Put another way: designating disrespect and denigration as beyond the pale, as grounds for exclusion from polite company, is ‘turning the temperature down.’ Klein and others are helping to turn it up.”

Someday, God willing, this moment of high temperatures may end. When it does, whether liberals have succeeded will depend a lot on whether conditions conducive to a healthy discourse have been restored. If we are left with a society where shaming moral indecency is itself socially discouraged, it will be an indecent society, no matter how civil the resulting discourse. If shaming bad-faith tactics is off the table too, the discourse won’t even be civil.

There is an even bigger thing. The fight about when to stigmatize is really about when morality matters enough to justify making things awkward. Muñoz tires of “mindless, nihilistic dunking”—but the truest nihilism is not shaming anyone for anything.

Morality is debatable, of course; but it does have certain universal elements that the New Right simply lacks.16 Altruism; empathy; tolerance; concern for others’ well-being. The people I think we should shame and mock are the ones loudly boasting that they don’t care about any of that.

You needn’t look hard to find them, on Substack or in the White House. They flout all conceptions of morality that incur upon them the slightest irritation or responsibility. They deride any effort to make the world better as “globalism,” and any effort to make the country better as unpatriotic. They starve our discourse of the evidence and air it needs to stay productive. pairing cruel beliefs with dishonest tactics. I owe them no respect.

Whine as they might, these people will never succeed in liberating themselves from other people’s judgment. Now and forever, most of society will look down on them. The inherent nastiness of the New Right is the very essence of what the word scorn was invented to describe.

The company I wish to keep has zero overlap with those who cheer that peaceful people will be tortured in a gulag for the rest of their life. To scorn these people is not even a choice. And I truly believe that people who support these things that should feel uncomfortable in our society. They should need pseudonyms on social media, because they’re embarrassed to say that shit in their own name. They should not be physically harmed or deprived of their rights—we are, after all, better than them—but it’s perfectly reasonable to ostracize them until they develop a moral circle broader than their cross-eyed field of vision.

Conclusion

I agree with Dan Williams that opposing the far right is not an excuse to indulge our tribal instincts, and I try to avoid that temptation. I reason first, argue second, and reserve my sharpest rhetoric for those whose reasoning seems flimsiest or least sincere.

But that is not a reason to avoid heated language altogether. Scorn and mockery are valid forms of political discourse that have historically played important roles in driving progress. However overused they may have been at times, today they are appropriate, politically useful, and even necessary responses to the beliefs and conduct of the sitting president. They are essential not only to winning the fight, but to ensuring we’re fighting for the right things.

In the short term, elite resistance to authoritarianism is a collective action problem. No individual is decisive, and given the state’s punitive power, it can be selfishly costly to stand firm. When the going gets rough, people get nervous and start eyeing their neighbors and colleagues for cues about how strongly to push back. Encouraging elites to tone down their rhetoric worsens this problem by weakening signals of solidarity against evil conduct.

In the intermediate term, defeating Trump at the polls will require us to drive a wedge between the New Right radicals who really are beyond the pale, and the moderate conservatives who aren’t. Scorn and mockery can be effective tools to do that, so long as they’re properly aimed. The stakes are high enough that it’s as important to use them as it is to focus their aim.

In the long term, shame and mockery help rebuild guardrails essential for liberalism to work. There is a field of conduct that must be deterred, without being forcibly coerced; stigma is how we do that.

Substackers love to whine about the wokes, and I love to fight random people who pop up in my feed. This combination of things has too often let my algorithm dictate my headspace. In 2026, I want to write less reactively and more intentionally, with a particular focus on how technology is transforming society; how AI may accelerate this transformation; and how tribalism impedes us from managing it responsibly.

As I’ve explained, JD Vance’s whole schtick is to carry on as if MAGA were intellectually defensible—and then when people point out why it’s not, to paint those people as incapable of entertaining dissent.

Likewise, the Ivy Exile on affirmative action: “The behavior of prestigious American institutions over at least the past twenty years can best be contextualized in terms of Rwanda: Hutus, Tutsis, and need for a truth and reconciliation commission.”

It is almost precious to imagine Donald Trump persuading anyone of anything, as if one iota of his appeal has ever come from force of argument.

This is also why they pretend 2024 were some landslide, realigning election (instead of what it was, which was a 1% victory over a uniquely dysfunctional Democratic campaign, at a moment of global incumbency disadvantage).

Conservative Substack’s obsession with the recent Jacob Savage article in Compact is this same pathetic, disproportionate fixation in action. Reasonable people can disagree on whether and to what extent minority applicants should have been favored over white male applicants from 2014-2024—and also to what extent they were favored, which is a separate question that surely varied by industry. As a white millennial man who got into two elite universities during that decade, it would be easy for me to dismiss the problem entirely—but I won’t. I’ve already written that I think DEI overstepped, and Savage’s piece provides a handful of statistics and anecdotes about specific newspapers or universities that update me to thinking affirmative action was slightly more aggressive than I realized in those venues (though still less prejudicial than society was against minority applicants for centuries, and less unjust than a dozen other problems that plagued our society during that decade). And in lieu of a measured response that keeps this problem in perspective, prominent conservative Substacker @The Ivy Exile opines: “The behavior of prestigious American institutions over at least the past twenty years can best be contextualized in terms of Rwanda: Hutus, Tutsis, and need for a truth and reconciliation commission.” They satirize themselves.

Some readers will confuse this paragraph as an argument for which thing should matter more to you, and accuse me of begging many relevant questions. It is not that argument. That argument would be devastating if I had time to make it; but all I actually have space for in this article is a summary of how I see you, based on the values I hold.

Neither writer is specific about where they personally draw the line, so perhaps they draw it the same place I do – somewhere between list A and B – and just have different priorities about which message to emphasize right now. In that case, the rest of this post addresses our differing emphases.

Since I first responded in September, Muñoz has written a follow-up piece that clarifies his views and gives a fair interpretation of Klein’s. In it, he distinguishes between drawing lines and policing them. It’s one thing to disassociate yourself from X person, he says, but another to demand others do the same. I have two responses to this.

First, it’s unclear what “police” or “demand” mean in practice that is so different from “draw.” Nobody thinks it should be illegal to interview Ben Shapiro. And part of me drawing my line is using my voice to say: “I think you should save your breath with this clown.” I am not even opposed to Klein interviewing Shapiro; but nor am I opposed to other people mocking Shapiro or the premise of the interview. It seems like Muñoz is opposed to that.

Second, surely some lines should be “policed,” even if we disagree on which. Would it be fine to publish a debate with pedophiles about whether raping children is okay? I agree we shouldn’t shame Bernie Sanders for going on Rogan’s podcast—but that’s not because I categorically oppose shaming anyone for going on any podcast. That’s just within my line.

Muñoz writes:

“Klein isn’t rejecting shame and pressure. He’s rejecting the “illusion” that we can use them to permanently vanquish our political opponents….”

But does anyone have that illusion, in 2025? It feels like 2024 shattered it for good. I think more liberals see shame and pressure as useful and proportionate tools in the fight against authoritarianism, which is an urgent effort even if we cannot permanently vanquish it any time soon.

One of my longtime guidelines is to address people with the same level of vitriol with which they address me. In the new right’s case, that’s quite a lot of vitriol.

In his interview with Ta Nehisi Coates, Klein admitted to feeling lost in his political analysis. “I don’t know what my role is anymore.” I admire him for admitting it, because that feeling is shared by millions in his tribe, and discussing it is key to getting out of our stupor. But I suspect the reason he feels lost is the same reason his prescription misses the mark: Ezra Klein is a rational man, who thinks about policy in a rational way, while the forces driving our country are not rational.

Importantly, this isn’t true of every conservative, or even most conservatives. As importantly, it is true of the administration Democrats will be running against in 2026 and 2028.

We can debate why this is (I think it’s tech); but regardless, winning campaigns will need to tap into it.

I agree with a writer called Degenerate Art, who thinks Klein and others have “gotten stuck imagining that we’re…somehow responsible for figuring the whole crisis out and having opinions on each new outrage and who should do what.” In truth, there is no grand solution. We will not strategize our way out of this. We’re not going to pick the right combination of issues to change Democrats’ perception in time for the 2026 Senate race; the arc of history is long, and social forces don’t work that fast. You can’t facilitate it. You are not in charge. Ezra Klein’s tribe is not even 10% in charge, and he can’t bring all of his tribe together anyway.

Anecdotally, my partner and I both have mothers who live in Pennsylvania who are fired up by Newsom’s Twitter game.

Every religion has the Golden Rule; our consciences object to similar images, etc.

The left can be combative, that’s fine. But what turned many moderates against it, other than just straight up bad policy positions on wokeness and immigration, was condescension and thought policing. People care less that you’re a lying asshole than if you hold them in contempt and try and control what they’re allowed the think. The latter is perceived as a greater threat than the former. So fight all you want, but stop doing it with an air of smug moral and intellectual superiority. It’s a fast way to make everyone hate you.

1. I agreed, in my post, that Democrats have used scorn too much over the past decade. Even if that were to blame for their electoral underperformance, it's compatible with my thesis that the optimal amount of scorn is above zero.

2. Besides, it's not clear - and begging the question - that Dems overusing scorn "caused them to lose" 2 of the last 3 elections. Both sides have used scorn extensively for each of the past 3 elections, and I don't think Democrats used any less of it in the run up to their 2020 victory than they did in 2016 or 2024. That suggests that elections are decided by other factors.

3. My main point is not that scorn is helpful to win elections. It could be in some circumstances, but I'm not confident about that. I think it's mostly irrelevant to elections. Rather, I think it's socially important that some conduct be shamed, so I need a compelling reason to silence my disgust towards that conduct. I don't need evidence that it's electorally helpful, because that's not the argument I'm making; where is the evidence that it's harmful, when directed towards the conduct I've described?